Thomas M. Sterner - The Practicing Mind

The core idea of the book is that practice isn’t the same as learning. The latter doesn’t imply the former, but the former does imply the latter. Practice is applied learning which requires a lot of repetition. Sports studies say 60 repetitions per day for 21 days. A related insight is that 10,000 hours doing a thing makes you an expert. The missing insight in both of those is that it’s not the outcome that matters but the process.

Why? Two reasons.

Firstly, you won’t spend the necessary 10,000 hours if you won’t feel like doing it. If practice is a sorry chore, you will avoid it. Therefore, to be successful, you need to approach practice from a perspective of having fun, from a perspective of lack of judgment, from a perspective of the present moment. You need to be mindful, you need to be aware of what is happening right now, and forget about your future plans and ambitions. Just like when playing a computer game, while the ultimate goal is to beat the game, the joy comes from the process of doing it, not from achieving the goal. The joy comes from flow, from focus.

Secondly, due to the happiness treadmill, you will never really achieve the outcome you want. Or, at least, the outcome you want today won’t bring you the happiness you think it should, when you achieve it two years from now. This is because with your perspective shift, and your new adjacent possible, your wants and ambitions grow as well. This is described in the book as setting a goal to “reach the horizon”. No matter how far you walk, no matter how far you sail, the horizon will forever stay away. Therefore, it’s important to focus on the process and forget the outcome. It’s important to think about the progress and not the goal.

This shouldn’t be depressing but rather liberating. Because it means we have the capacity for infinite progress. That no matter what goal we set, we can beat it, and continue progressing. This shift of perception creates the patience that’s needed to discipline ourselves to perform the practice. Even unforeseen circumstances that complicate previous plans can be perceived in a patient way, by reacting to them with a “this is where the fun begins” mindset. That’s a Han Solo quote by the way.

The author suggests employing constant feedback to one’s behavior through what he calls a “DOC” cycle: Do, Observe, Correct. This is in fact something that I’ve seen corroborated by other books on habit forming and practice. The way to get better is not only through repetition but also through constant course correction. The easiest form of employing that is to have a personal trainer in whatever skill we pursue. That person is able to observe more and suggest corrections based on their previous experience, both first-hand and seen in other trainees.

When working alone and planning to “eat the elephant” (execute an overwhelmingly large task), the author suggests the “Four S” mnemonic:

- Simplify: find a single attainable goal that is on the path to completing the big project and focus only on that one until you complete it;

- Small: chop this attainable goal into sub-tasks where each one doesn’t take too long to complete and it’s clear what “complete” means for it;

- Short: now you can start executing your sub-tasks one by one – plan to execute them in short time boxes, 30 to 45 minutes, this is the easiest way to convince our self to actually do it; and

- Slow: actively fight against the urge to rush ahead, stop your ego from raising anxiety; perform each step with care, slower than you feel like initially doing it.

This last one is rather poorly explained through an example where tuning a piano by doing everything super slow turned out to be faster than the usual process that the author performed over years of professional practice. Hard to believe and likely not transferable to other areas of life. But there is a good way to explain why “Slow” still makes sense, which the author also is surely intimately familiar with. When you train something, be it a technical part in a music piece, or dancing tango, or archery, you don’t expect to be able to perform the task skillfully in full tempo on first try. There is a learning process, training of muscle memory, that we need to go through. It’s not uncommon to play a piano piece over twice as slow initially when learning it.

This applies to any pursuit in life because, as the author points out elsewhere, even the skill to practice is something that needs practice. There’s some uncomfortable recursion or inception here but it’s true. We need to learn how to learn, and we need to practice practicing.

It wasn’t easy for me to identify with the author. He is not an everyman. He holds a pilot license, his wife’s father owns a golf course, throughout his life he was able to consistently outrun his peers in discipline and perserverance, as he points out in a few stories from his past. Is such a person really able to instill disclipline and focus in people who struggle with it? I’m not sure.

Plus there are unnecessary hints of religion in the book, like the concept of an eternal “true self” that is “forever”, that distract from the core subject matter. The second half of the book shifts to being essentially a praise of Vipassanā-style mindfulness. All throughout the book there are bits of naive fascination with “the Orient” and Far Eastern philosophy, exemplified for example by praising Japanese care of process over results, while there are numerous examples of this trait being practiced less than, say, in San Diego.

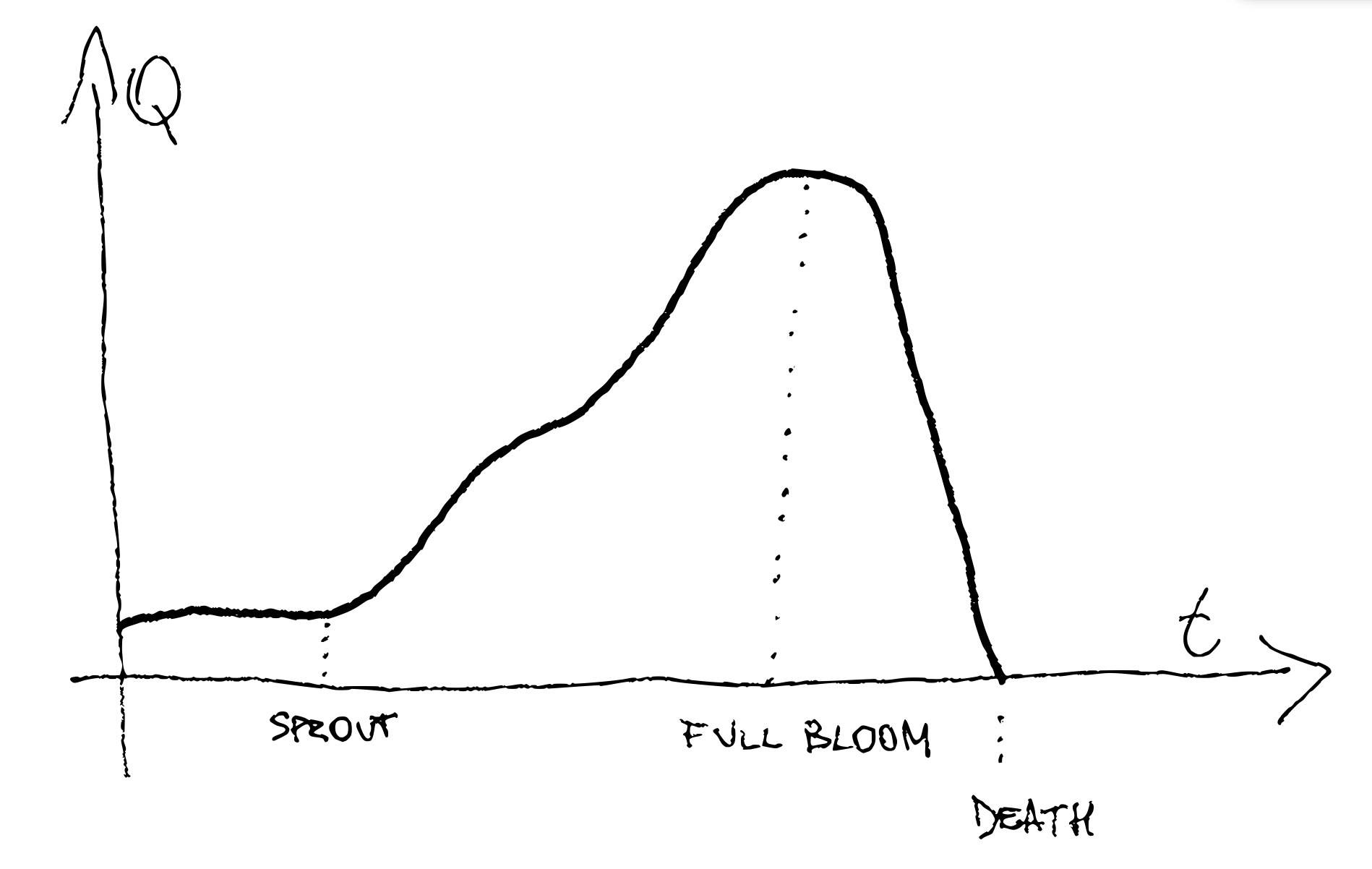

One other area of my disagreement with the author comes where he is trying to convey the message that “each skill level is equally wonderful and enjoyable” through a flawed analogy. He is asking “at which stage in the flower’s life is it the most perfect?”. His pushed answer is that it is perfect at each stage but this is wrong in an obvious way. I would rather draw a flower’s life like this:

First, there is some potential to the seed until it sprouts. The plant starts growing and increasingly looks like a flower. At some point it reaches full bloom, around which time it is probably the largest, the most colorful, most fertile, most efficient in turning light, water, and soil nutrients into energy. It is at its obvious peak. From then there’s decline, decay, and eventual death. Some flowers never reach full bloom due to poor environmental conditions (too little light, not watered enough or watered too much, poor soil, too windy, too cold or hot, and so on) or misfortune (pests, getting trampled or plucked). Some might be genetically flawed.

The author’s analogy was obviously a forced attempt at saying that We Are Enough at each step of the way and that there’s potential in us from the beginning. But it’s an analogy flawed enough that we can go too far with it and looking at it, compare it to human life. Then you’d protest at my blunt graph. How can children be less perfect than adults! How can senior citizens reach a point where they are worth less than a fetus! Yeah, I’m not going there, I’m not drawing this parallel. As I said, it’s a bad analogy. There’s nothing controversial in saying that I’d rather eat a ripe strawberry than a green one. There’s nothing controversial in saying that the reason kids get inspired by soccer, guitar, or astronomy, is because they look at Cristiano Ronaldo, Jimi Hendrix, and astronauts in rockets flying to space. In other words, they get inspired by how state-of-the-art looks like, by the pinnacle of achievement.

All in all, the book is short enough that I would recommend reading it regardless of its flaws.